With the looming Trump Trade War in the background, I’ve been working through stuff I accumulated over the years and every so often, a forgotten nugget pops up. From 1985 to 1992, an automotive trade magazine (Chilton’s Automotive Industries – now Automotive Industries) sponsored an competitive event that pitted auto manufacturing plants from different companies against one another. The magazine editors went to different factories in different companies and timed how long it took to change the “die” in an auto body stamping press. You can read the full originals if you can track down back issues of the magazine in the stacks of a research library. I think I remember that it was always the June issue each year.

What is a Die Change and Why is it Important?

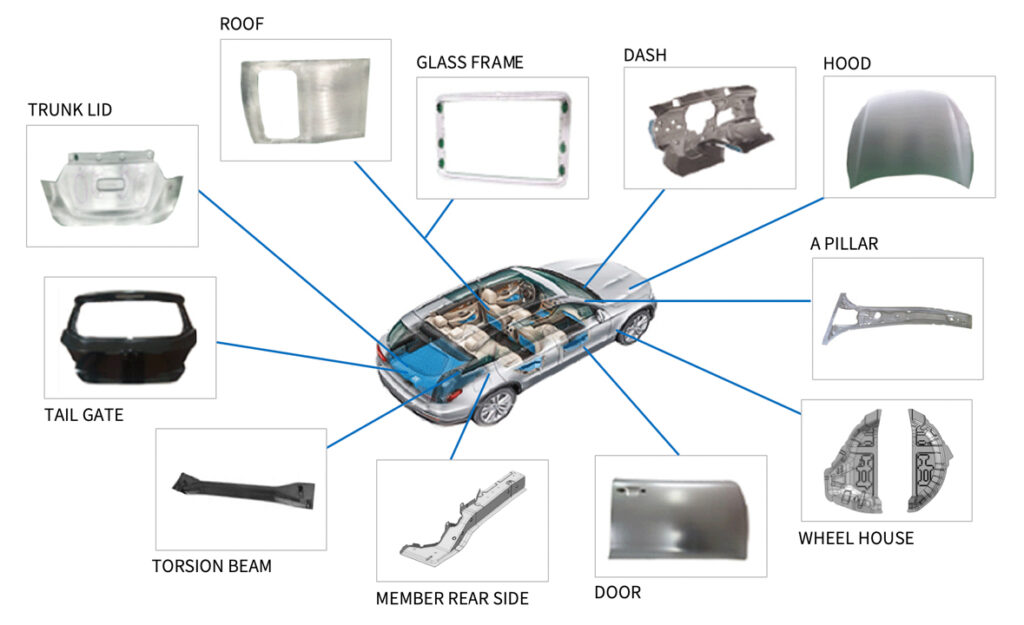

For many large manufactured products, such as automobiles, factories must shape sheet metal parts to form the product’s structural shell. This diagram shows some of the types of car parts that are usually made this way.

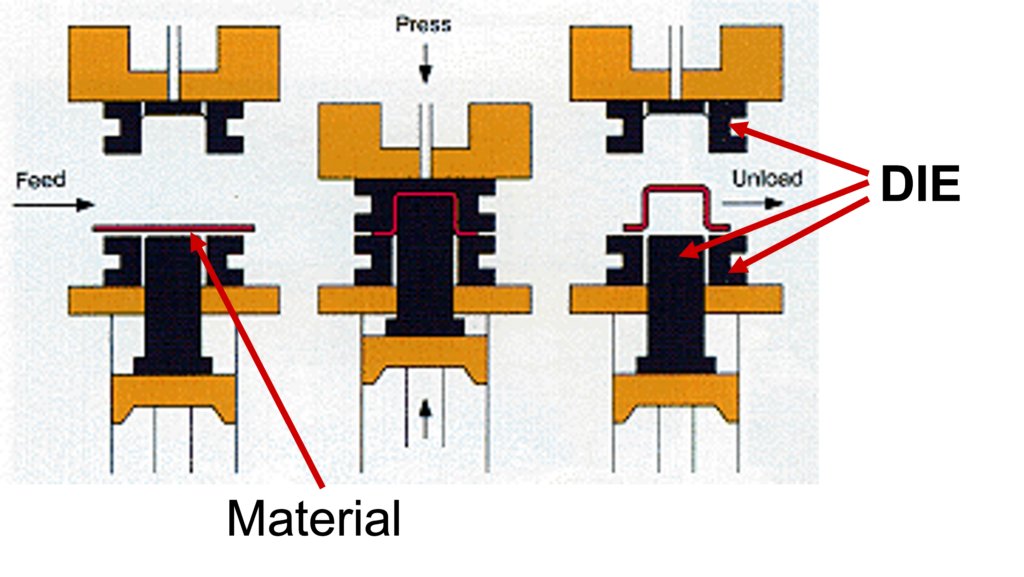

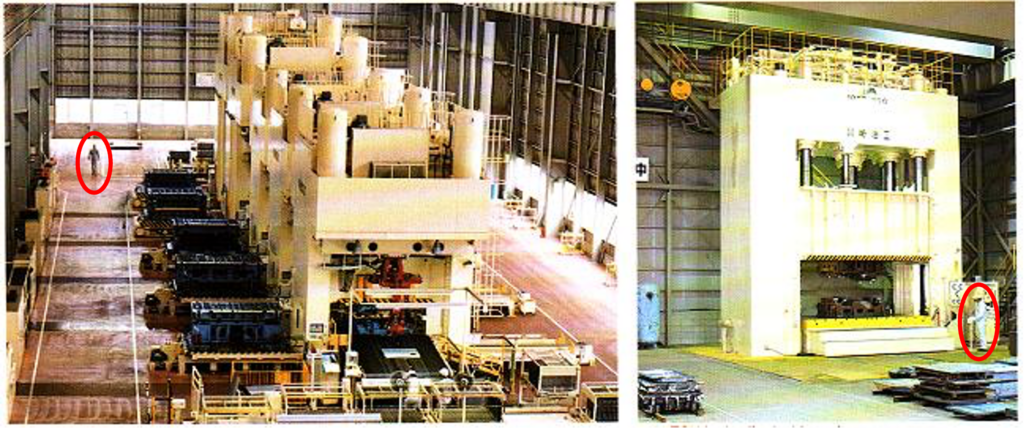

These parts are made by pressing (stamping) a sheet of metal between two carefully shaped surfaces (collectively called the “die”). This is done in massive stamping presses that can generate hundreds or even thousands of tons of force. You can judge the scale of these machines by the people circled in red in these photos.

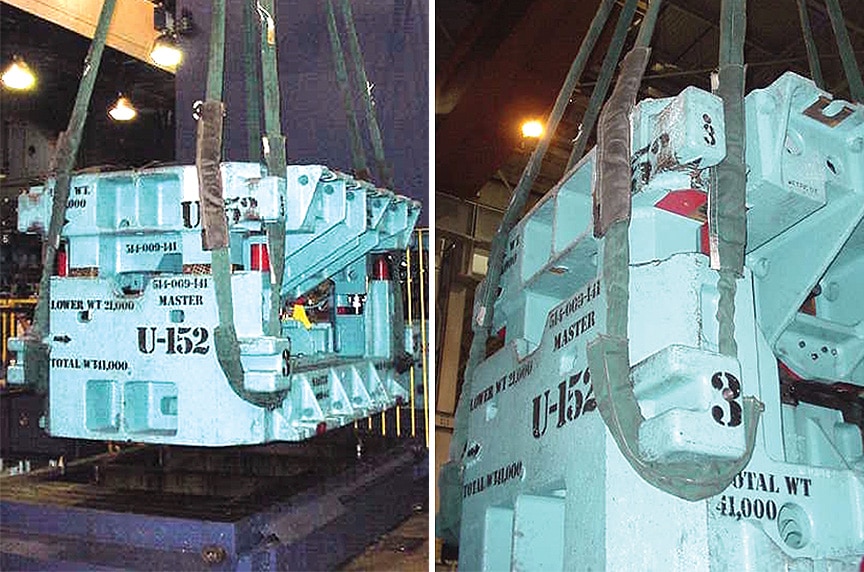

The machines press shapes the part by pushing massive metal tools (dies) together (top to bottom) to squeeze a sheet of metal into the desired shape, possibly including holes and punched out areas. The dies themselves are massive: 10 to 20 tons each. You don’t pick them up and place them. You use heavy equipment to even budge them.

Photos of Typical auto scale stamping dies.

Die changes are crucial in the auto industry because they control how quickly an automaker can switch models. The old days of Henry Ford saying “you can get it in any color you want as long as it is black” are long gone. To give an idea, a 2020ish plant can dial in any one of several body options and myriad combinations of accessories virtually on a car by car basis. It is totally normal to see a blue car followed by a black one, then a white one on the same assembly line. That is impossible if it takes a long time to change from manufacturing one part to another. In the bad old days, long changeover times caused factories to make thousands of the same panel before changing. All of the units went into storage until called for. The problem is that a change in sales patterns could leave many of those as unneeded scrap.

Plus, body panels are often the bottleneck in the process. If you look at modern assembly plants, you will generally see a big building with no windows at the start end of the process. That is the stamping plant, which is big and expensive and not something you are likely to expand or duplicate on a whim.

1985 & 1986

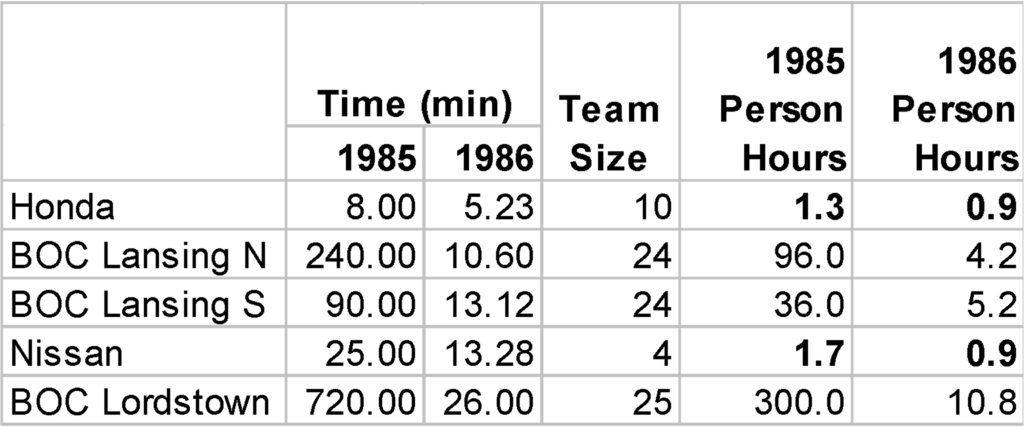

The contest began in 1985, when Chilton’s Automotive Industry staff (CAI) visited five factories from three carmakers. They used a stopwatch to time how long it took a team in each plant to swap the dies from one part to another. They started timing when the last prior part left the press and stopped the watch when the first of the new part was ready to stamp.They also noted the team size, so I have added the person-hour calculations. That is a rough indicator of the cost of the change.

In addition, CAI added editorial comments about the processes they saw. I, in turn, summarized a selection of those into a few bullet points.

Buick-Oldsmobile-Cadillac (BOC) Lordstown OH

- 17-year old manual press

- One of the worst labor-management histories in the auto industry

- “These guys have barely inches to spare as they swing to and fro with massive die trucks that weigh thousands of pounds apiece. The slightest misjudgment and they’ll smash the side of a press, or crush a die. Yet, they make it look easy. I shake my head. This is industrial ballet.”

Honda Marysville OH

- Semi-automated 4 yr old press

- “Sometimes we make three die changes per shift. I feel there are fewer problems on a quick die change than when you just take your time. It seems that everything just falls in place. When you’ve only got five minutes, you don’t have time to think. Everything has just got to be there.”

BOC Lansing North

- Semi-automated 3 yr old press

- “We realized we needed more uptime to be competitive and die change was the most obvious point where we were behind. With that uptime we now have lots of capacity to bring work back in from non-GM plants.”

- “Our success in the future hinges on our ability to be flexible and respond quickly so we can go after low production vehicles.”

This exercise established the baseline for the competition and improvements that followed. It also illustrates the huge edge that the Japanese plants held over their GM competition. Note the huge reduction in time at BOC Lordstown once it saw how far off it was.

1987

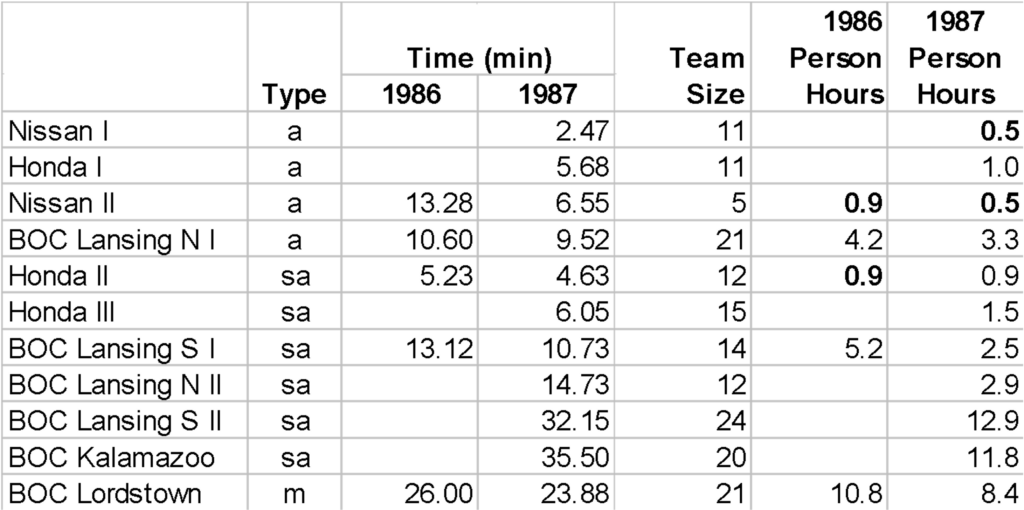

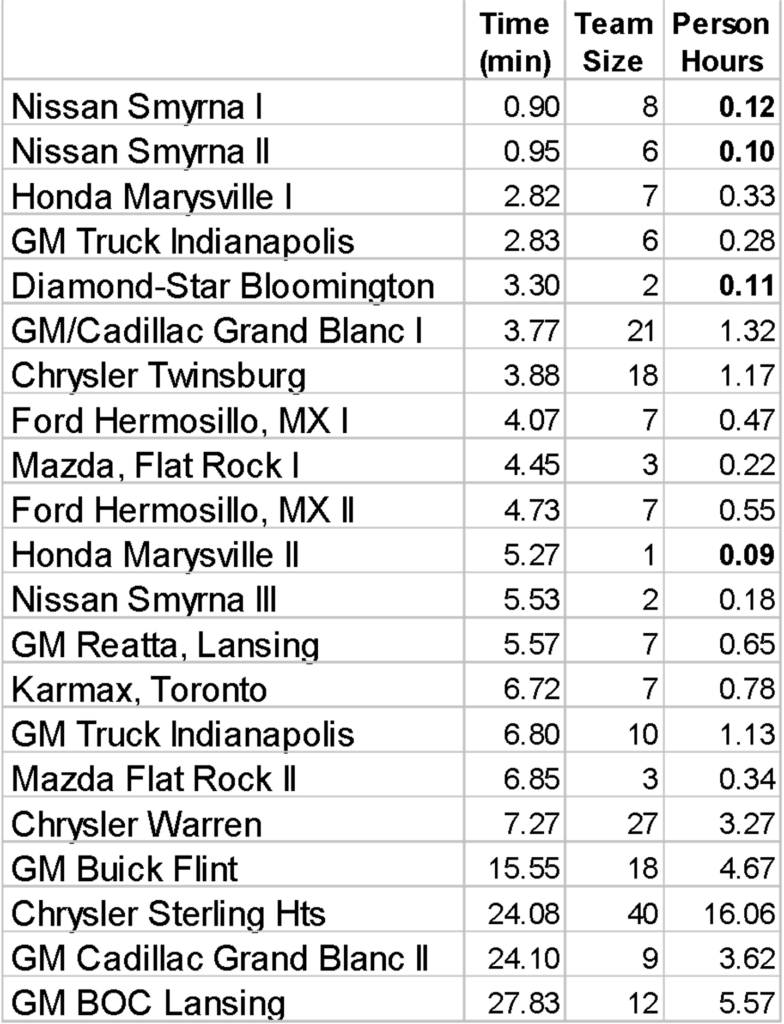

The articles apparently created struck a chord in the companies. By the next year, Honda, Nissan and BOC had entered more plants as competitors. They also reported the type of press: a) automated, sa) semi-automated, and m) manual.

Nissan Smyrna TN

- Five tandem press changed in 2:28

- “Ten men and a woman meshed with the precision of an all-star NHL line on a power-play drive. They had darted in among the big Hitachis to break down the existing die setup, before the new dies rolled methodically into place…”

- “Talk about cool under fire; this team, which normally knocks off consistent 10 minute die sets (sometimes five a day) re-defines the term.”

BOC Lansing North

- “Changing dies is a labor intensive operation. Doing it fast requires coordination, cooperation and smarts. Interestingly, the downloading of software into machinery has proven to be one of the limiting factors.”

- “… plant operations head, Mike Camp boasts that never before has any GM plant in the world changed four major die lines in half an hour or less.”

The progress in all plants was striking. BOC still lagged the Japanese automakers, but the gap closed substantially.

1988

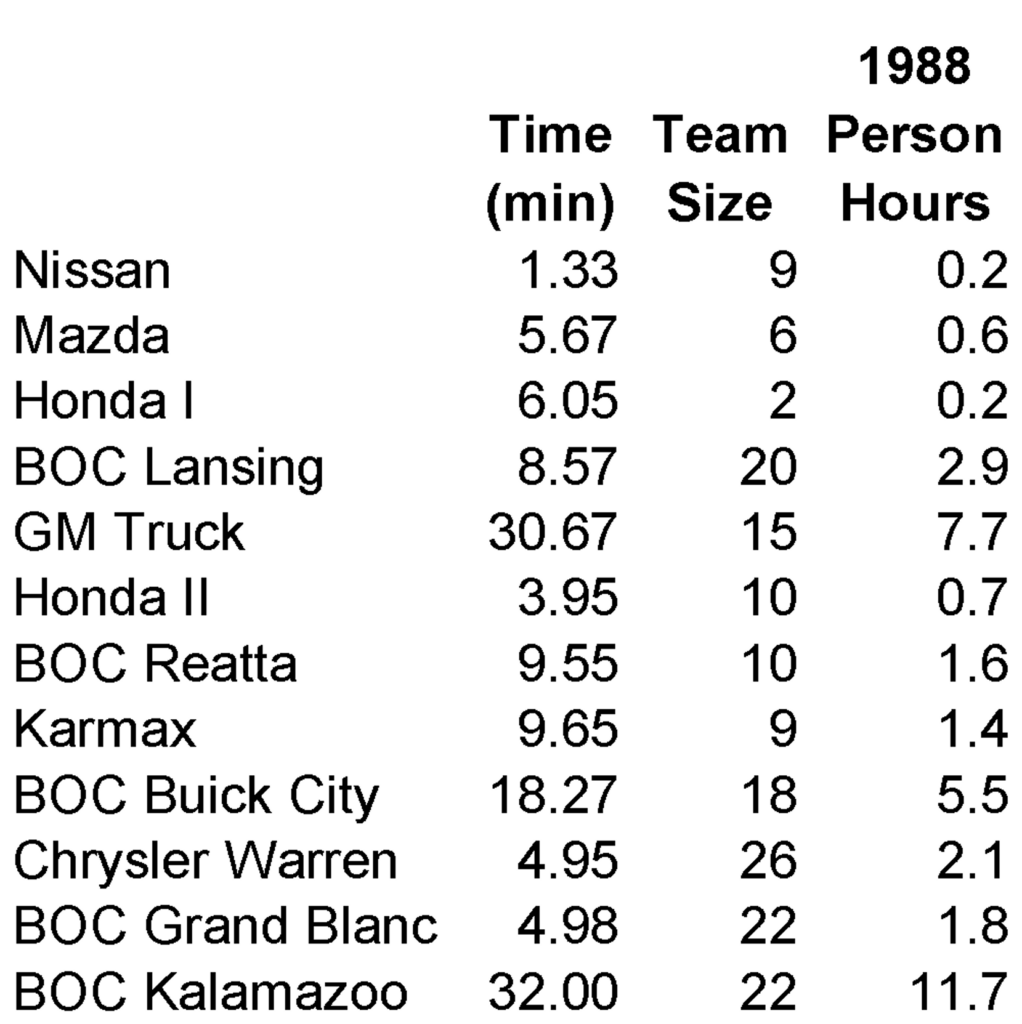

The competition must have stirred some strong reactions in the industry because Chrysler, Mazda and an independent supplier joined the fray. I sense there may have been some serious bragging rights at stake.

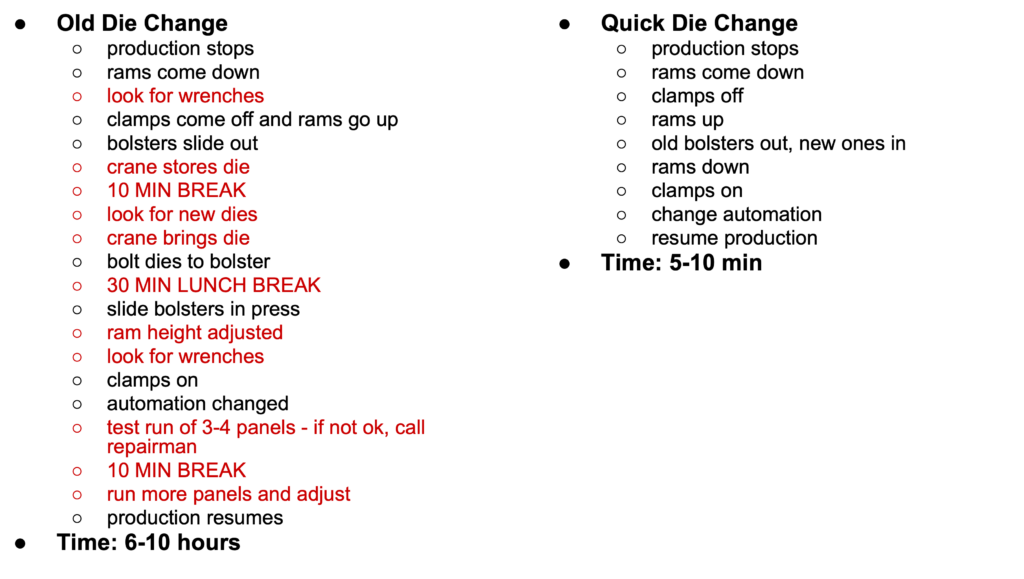

1985 vs 1988 at Lansing North

The editors decided to take a look back to see the progress for the same press at the same factory. As I recall, the “old die change” was the original 1985 process. Gotta say, that was ugly. However, three years later it is hard to recognize that it could be the same process. No question, an American company really upped its game.

1989

By now, the field had increased even more. Note that two Mexican plants and a Canadian plant show up for the first time and they aren’t too shabby.

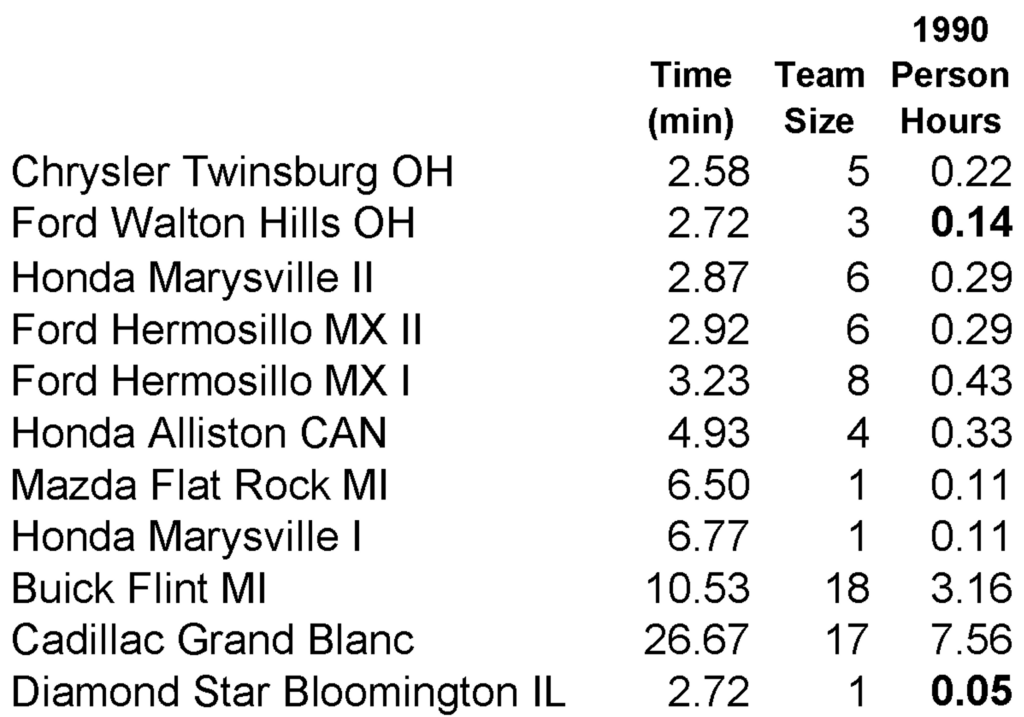

1990

Even more companies joined the competition. Also, if doing the change fast and at the lowest cost (as measured by team person-hours expended) is the criteria, an American factory was in the lead. Diamond Star was a Chrysler subsidiary. As a sort of “vendor” they didn’t just supply one plant. They served several. Orders could change at any time, from any direction.

The emerging trend was not just to do fast changes, but to do them with minimal (sometimes only 1 person) change team. Note that this progress seems to be approaching a limit. How can you do much better than making the change in less than 3 minutes with one person?

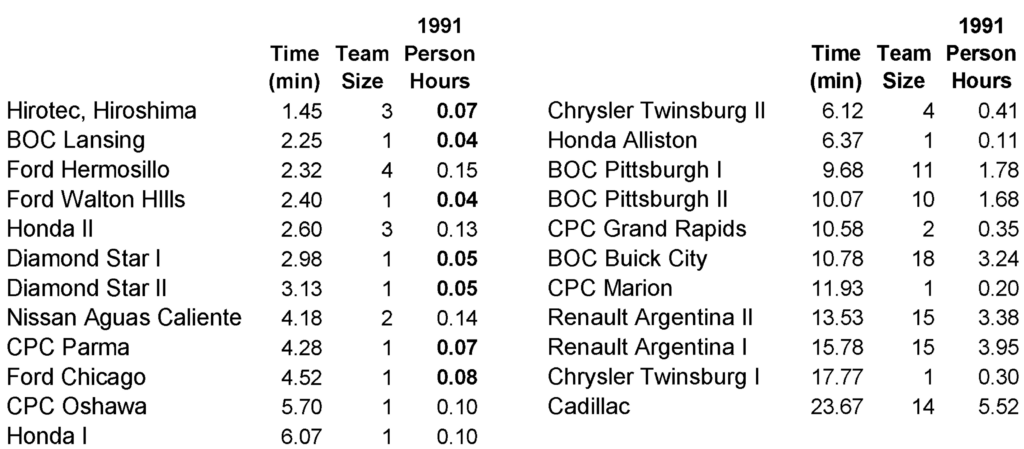

1991

This is the high water mark of the contest. Competitors entered from all of the Big 3 companies, plus plants in Mexico, Canada, Argentina and Japan. That’s a decent sample of everyone relevant to the North American car industry. There are plants that are faster and plants that use fewer operators, but all of the competitors, with the possible exception of the Cadillac plant, were close enough that the differences weren’t important in terms of factory production efficiency. They were all more than “good enough”.

In six years, the performance gap between competing automakers was effectively closed – on time, staffing levels and cost. This was due to pure competition of the type you routinely see in major league sports. Just good companies going head to head. American companies started behind, but they definitively caught up and often passed their Japanese competitors.

1992

With little more to gain in speed or staffing, CAI changed the rules and stopped listing change times. Instead, it created a three-part scale to factor in production quick die change, press throughput, and quality. Hirotec won, followed by AutoAlliance(Mazda) in Flat Rock, then Honda, then General Motors plants. From an audience perspective, the contest had become a bit boring.

1993

Automotive Industries claims that it was the victim of downsizing in the editorial offices, so they discontinued the series. Probably inevitable, but still a bummer !

My Take Aways

When I started teaching Operations Management at Auburn University in the early 90s, I made a slide deck about this competition. AFAIK, this contest is a complete unicorn. To this day, I’ve seen nothing else like it … it offers a stopwatch-accurate record of real-life manufacturing performance between competing companies.

Despite the fact that it is 30 years old, I think this story holds important lessons for current manufacturing professionals and students. Most of my university students had little or no sense of how automotive companies competed on manufacturing. Nor, I suspect do the vast majority of people who haven’t worked in this type of industry. Even the people who do work in these plants typically only know how their factory works. For that reason, I would add the following suggested takeaways:

- Competition in technical industries (which is now most of them) is far more complex than just cost or headcount. Things like creativity and teamwork are often as or more important.

- Automation matters. In many cases, it is an overwhelming advantage. That means that companies need to make the investments to buy or develop the world-class automation that they need.

- Even the worst companies can get better in a hurry if they have a clear target and the will to pursue it.

- Nationality doesn’t mean much. Smart, hard-working people anywhere in the world can raise their game to the top level.

- Look at how far the labor inputs fell over the course of this period. From over 100 person-hours in the worst plants in 1985 to less than 0.05 person-hours in 1991. That had nothing to do with pressuring workers. It was a combination of process improvement around huge strides in automation. By 1991, labor cost was almost an irrelevance in sequencing stamping of auto body parts.

Finally, to me, this has important implications for the threatened Trump Trade War. If this is a true face of manufacturing competition, will tariffs help or hurt? IMO, I would hate to see American companies insulated from this type of competition. They won’t get better fast enough if they are sitting fat and happy behind tariff walls. When competition eventually sneaks in, they will be hopelessly behind. It is especially troubling because this story gives me great confidence that properly motivated American companies can slug it out successfully with the best in the world.

I am sure readers will have their own takeaways, disagreements and questions. I sort of wish we could prevail on Automotive Industries to dig this out of their archive and dress it up for broader viewing.