March, 2000 witnessed a crisis in the gun industry. I’ve been researching and teaching about business operations for 40+ years and I can’t think of any other industry-wide event that exhibited the sheer savagery of the gun industry’s collective public destruction of Smith & Wesson.

S&W was the last big American gun manufacturer to make a principled effort to limit gun violence. Their CEO, Ed Schultz, signed an agreement with the Clinton administration to establish a “code of conduct” that implemented better traceability and limits on sales to prohibited persons. It also agree to strive for adoption of a “smart gun” concept, where guns are rendered inert except in the hands of their owner(s).

Within a year, competitors, suppliers, distributors, customers and the NRA applied a boycott that crushed S&W sales and forced Shultz out of the company. The company, which had been bought in 1987 for $113 million, was dumped in May 2001 for $15 million and the Clinton agreement was scrapped.

This and other gun industry anecdotes are described by Ryan Busse, a former high profile gun marketer, who recently published the book, Gunfight (available from Amazon). You can read some of his thoughts for free on his Twitter account. Busse’s stories give fascinating insights into gun industry culture, but to my mind, they don’t explain how an entire industry could organize to act in such a choreographed, cohesive and brutal manner. Then I stumbled on a Twitter feed by Dan Kaszeta that notes how the gun industry is structurally different from most other tech goods industries.

You can read Dan’s thread to glimpse some of what I discuss below, but paraphrasing Dan, the gun industry faces the following dilemma:

The gun industry annually sells $20 billion worth of guns, even though Americans already own 300+ million guns that seldom wear out.

This contains two interesting mysteries about the gun industry’s structure and its operations:

- How does the gun industry grow if its product doesn’t wear out and its market is saturated?

- Why did an entire industry: vendors, customers, and trade association (NRA), form a mob to destroy an iconic industry member in less than a year?

To answer these questions, I’m reminded of a line from Sherlock Holmes: “when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth”. So let’s try to eliminate some impossibilities in gun industry’s operations by comparing it to other durable goods manufacturing industries like autos, appliances, etc.

Who Buys Guns?

To understand a product industry, you need to start with sales. Ultimately, that’s where the money originates.

For an automaker, most sales are replacements for cars that owners consider worn out or obsolete. Replacement sales provide the stable income base for a capital intensive, durable goods industries. That’s why automakers work so hard to retain brand loyalty.

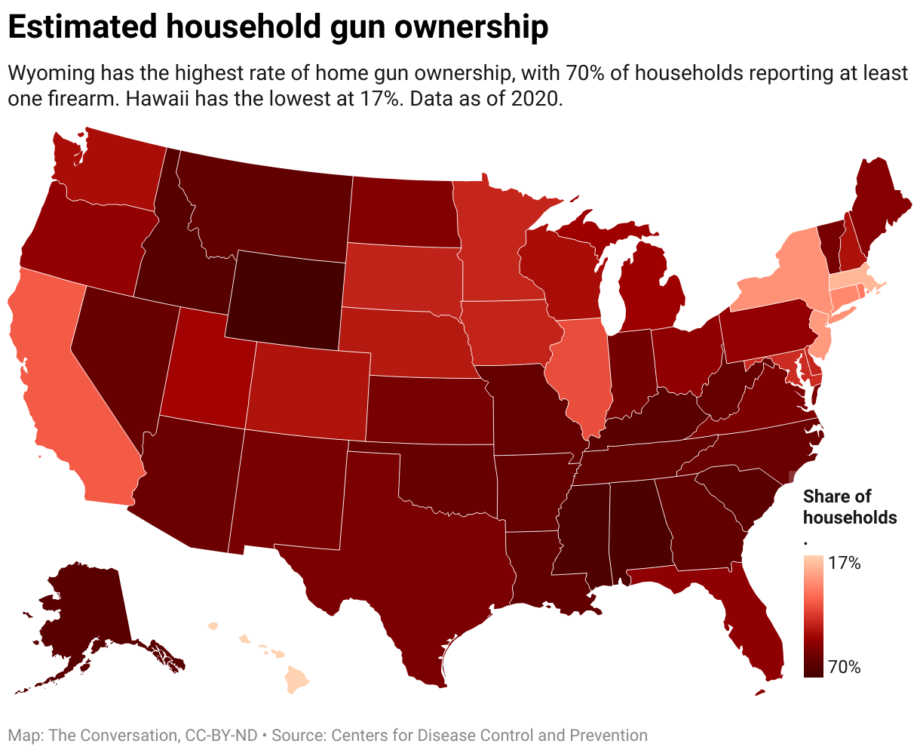

In the gun market, the “wear and tear” replacement market is small. For example, you don’t see gun industry equivalents to the auto “wrecker yards” or used auto parts distributors. Unused guns just go to the back of the gun safe. Therefore, the gun industry must make its annual sales numbers by selling more guns to existing owners and by attracting first-time buyers.

However, if you meet this year’s sales goals for new customers, next year they will be existing owners. To grow year over year, you must range farther afield and construct ever more creative sales stories to capture untapped prospects. Then, when they become gun owners, you must find ever more compelling reasons why they should expand their existing arsenal … IOW the gun industry sales math gets harder every year.

The Gun Industry Seldom Really Innovates

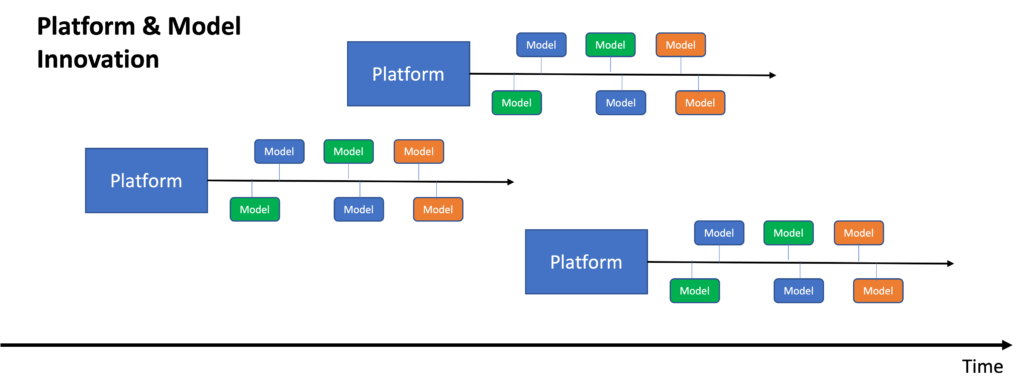

Faced with market saturation, other industries turn to innovation. You offer “new and better” designs. Your customers don’t replace their products because they’re worn out, they buy new units because they are better than what they have. Back in the day, I studied management of technology (my PhD) and business operations. I even co-authored a university textbook on managing product families that modelled the mechanics of this type of product innovation. For manufactured devices, the design cycle is typically a synthesis of two processes.

Periodically, a manufacturer will design a new “platform”. For cars, new platform designs can cost many billions of dollars and are only done if the automaker has a major change in mind. Otherwise, year to year, the changes are new “models”. The models may appear innovative, but they don’t require extensive retooling or re-engineering and the marketing campaigns hype up the minor changes to make them seem more significant than they really are.

This works fine if you’re replacing tired vehicles and serving a few first-time buyers. However, it won’t entice owners to buy a second or third vehicle or make them replace a vehicle that still works well. For that, the automaker must introduce a periodic “platform” changes. That’s the type of change that occurred with the first minivans, SUVs, hybrids, luxury pickup trucks, and electric vehicles. They had feature sets that were so dramatically different that owners willingly discarded older vehicles even if they were still functional.

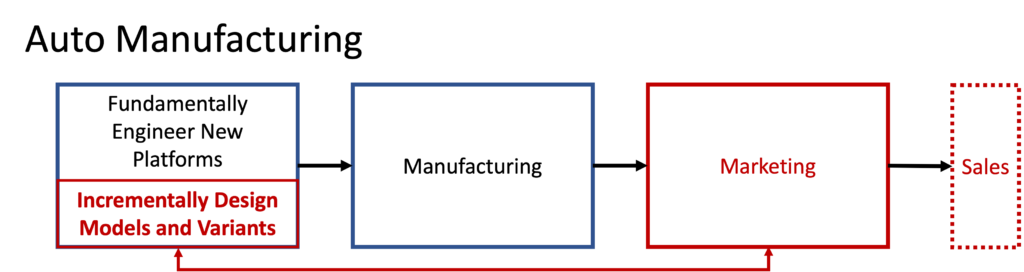

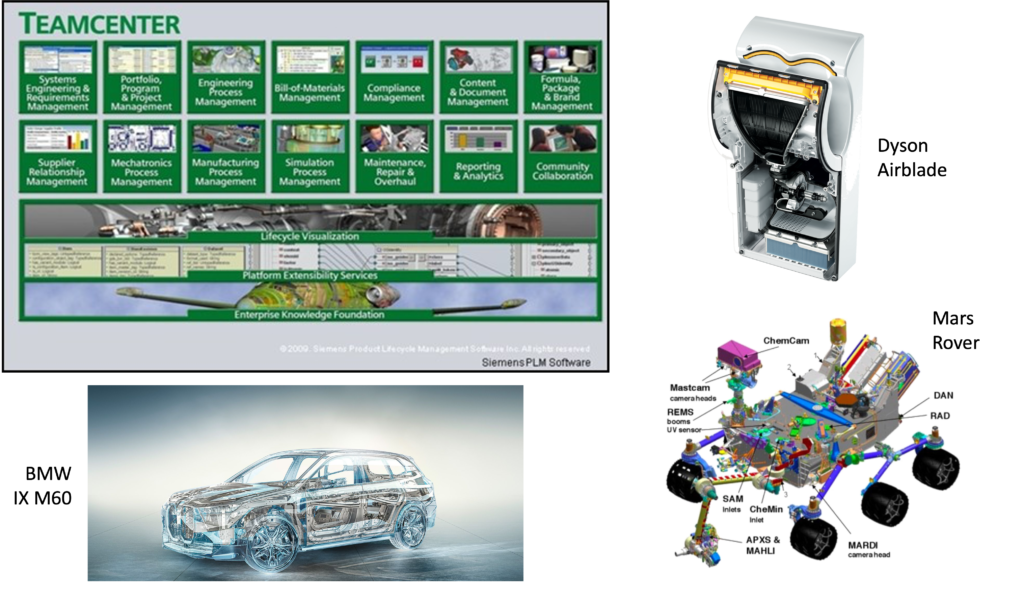

To run a platform-model system like the auto industry, you need an integrated design, manufacturing and marketing system. The following diagram is the simplest version I can suggest. It shows a four-step process. Design the car. Make the car. Develop a sales story for the car (marketing). Then sell the car. There is a natural feedback look that connects marketing to the follow-on incremental model changes.

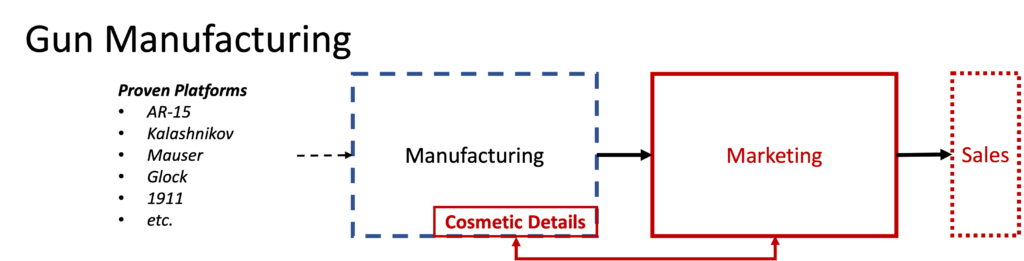

The gun industry is very different. Not only are its finished products distressingly durable, it offers far less room for major platform design. Its biggest selling guns are mostly built on a small number of very long-lived platform designs. Those platforms originate from military weapons like the following:

- Browning 1911 automatic pistol (1911)

- Russian Kalashnikov AK-47 (1947)

- Armalite Rifle AR-15 (1962)

- Glock 17 (1980)

- etc.

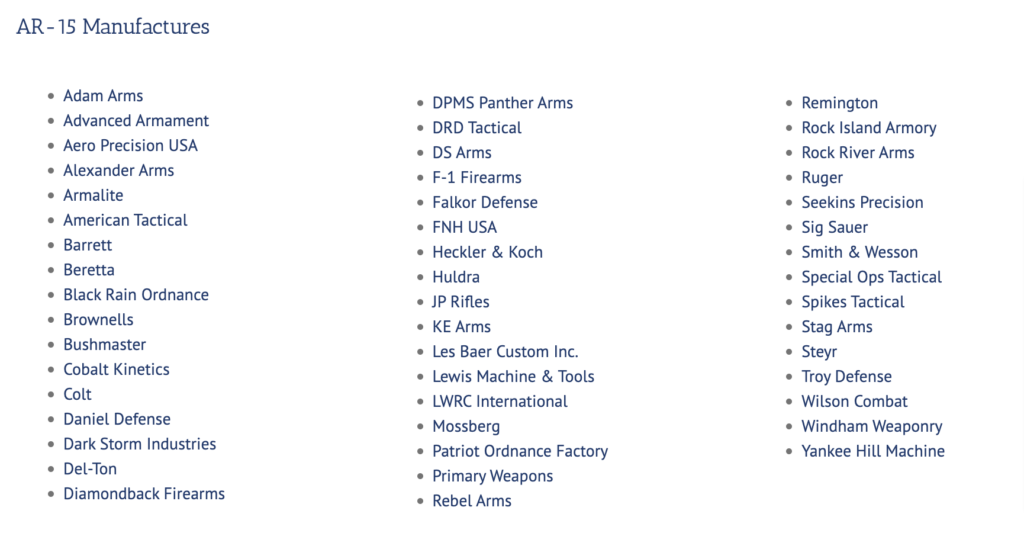

When these designs worked well in military and law enforcement applications, they were introduced to wider civilian use, typically after their patents expired. For example, many companies make rifles around the AR15 design platform. They adopted the basic mechanics of the 1980 design and made changes to the attachments and accessories. The following list was compiled in 2016:

As the next diagram shows, while there are differences, the basic design pattern is recognizable throughout. Also, with consistent metalwork design, the manufacturing processes are very similar. There is no technical reason why the top AR15 makers should differ much in features or manufacturing cost.

For a more detailed feel about gun industry innovation, I’ve linked a video “teardown” of the civilian version of the US Army’s new (2022) M5 assault rifle. The Army just ran an open design competition and awarded a $1 Billion contract to German-based Sig Sauer for rifles to equip US Army combat soldiers. I don’t recommend watching the full 35 min video unless you’re a mechanical engineer or gun geek., but you might view a random minute or three, then consider the wider implications.

If any rifle should reflect the best of gun industry innovation, it ought to be the new rifle for US Army combat soldiers. However, the M5’s level of innovation is barely measurable. Compare it to the kinds of systems innovations that are routine in most other manufactured products. I spent a few years writing sales eLearning courses for Siemens PLM. The following diagram shows the comprehensive software tools that are now standard for complex manufactured products. Products from companies like Dyson, BMW, NASA, and Airbus are conceived, designed, virtually tested, manufactured, and serviced with software like this.

This class of software typically starts with an industrial-strength CAD system and then embeds tools and simulators for heat transfer, aerodynamics, electrical circuit performance and a host of other sophistications. It’s hard to see how an AR15 pattern gun would need even 5% of this capability … and only then at its lowest level of capability. As far as I can see, gun makers’ changes are so minor that they’re barely more than marketing and manufacturing tweaks. Case in point:

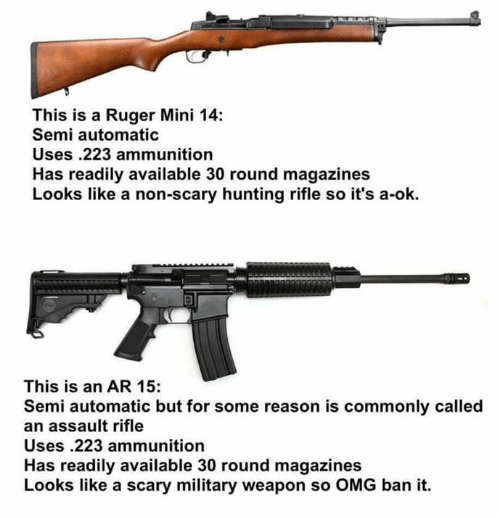

This image is typical of a meme that has floated around the Internet since the 1994 Assault Weapons Ban. It tries to prove that assault rifles are just normal rifles in fancy dressup. The Mini14 (wooden stock) is derived from the M14 that entered US Army service 1959 and, in turn, was derived from the WWII M1 Garand rifle. Hence, its core design is arguably 75+ years old. When it suits them, the gun culture claims the AR-15 is nothing new. When they want to sell new guns, the gun culture will wax poetic about the clever placement of the swivel for the carrying strap.

Mars Rover they ain’t.

Marketing Fairytales

If you eliminate what is impossible (design, innovation and manufacturing advantage), whatever is left (marketing story-telling) must be what is happening … and so it is for the gun industry: Gun makers must sell to a saturated market and attract new prospects by marketing almost exclusively to subjective wants and needs.

Everyone who observes guns in America will have a different impression of the gun industry’s marketing strategy. For what it’s worth, I believe that the gun industry is pursing the only path it can. Since its products are not innovative, it wraps them in provocative sales stories to excite naive buyers. These are the people that can be fooled into thinking that everyone is out to get them and/or a gun will make them into a hero.

IMO, the gun industry marketing strategy is four-pronged: a) amplify fears of violence from “others”, b) reinforce heroic fantasies about confronting the “others”, c) piggy-back on any convenient form of extremism, and d) lobby government to expand the pool of naive people authorized to buy and carry guns.

A Fear for Every Demographic

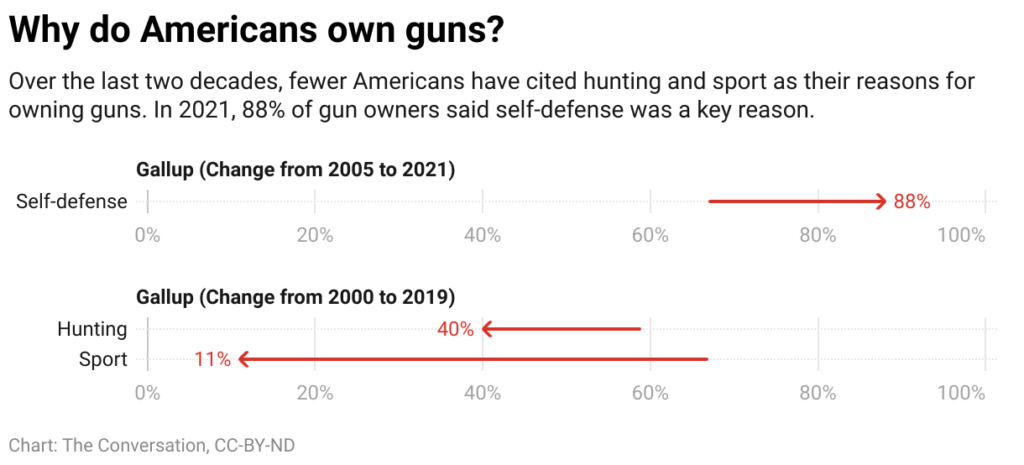

There are remarkably few polls and studies of American perceptions of guns and the gun industry. The gun industry has worked hard to discourage government and academia from doing legitimate research on the subject. Nonetheless, Gallup has been doing a modestly useful survey for a few years. The following diagram shows the shift that has occurred in America’s gun owners’ perception of the fundamental purpose for owning a gun.

In the past two decades, the traditional reasons for gun ownership (sport/target shooting and hunting) have decreased dramatically. Meanwhile the belief that guns are needed for self-defense has exploded. Nearly 9 in 10 gun owners now think that their guns might be needed to fend off a potential adversary. This has profound implications for gun marketing and is truly a team effort. The industry, the gun culture and their Republican enablers have made “fear of others” the centerpiece of their political discourse. Not just fear of others’ viewpoints, but a mortal terror of others.

The practical impact is to convince a 40 year old mom that she needs a gun to defend her home, even if she lives in a suburban gated community. If she thought about it in 1995 terms, she would worry that her children might find the weapon and harm themselves. Now, she’s afraid that an intruder (presumably POC) will rob or rape her. The fear is objectively irrational, but repetition makes it seem very real. Similar fears are inflicted on many other demographics.

The truly depressing aspect of this fear-mongering is that the industry must sell more guns next year, and more the year after, so the industry will (and must) continually amp up the fears. The absurdities of industry fear-mongering are essential to gun industry survival. It must reinforce existing fears and continually invent new and more frightening scenarios.

- Americans fear of being oppressed by a tyrant.

- Whites fear of attacks by POC and Antifa

- Everyone’s fears about violent crime

Cosplaying Heroic Fantasies

Several years ago, I was a passenger with a long-time colleague driving to a meeting in the Deep South. As we returned on the Interstate, a car passed us driving erratically. weaving abruptly from the shoulder to the middle of the left lane. After a minute or so, I called 911 to report the car and give its license. Then it raced ahead and disappeared, at least 40 mph over the speed limit. Five or ten miles later we saw a cluster of cars on the shoulder with hazards flashing. As we approached, we saw the errant car had skidded down a grass embankment and stopped about 50 ft from the road.

My colleague stopped, reached across, pulled a Glock from the glove compartment, and ran down to the car. I started to phone it in just as a State patrol car arrived. My colleage stopped and walked back, put the Glock away, and resumed driving. His only comment was that anyone impaired enough to drive like that might have been violent. I want to stress that he wasn’t an obvious gun enthusiast. He had never mentioned guns in years of daily conversation.

I’ve thought about that incident periodically. The odds of meeting a stoned, maniac gun owner (let alone one who was that impaired but could still shoot straight) were remote. Plus, if he was really motivated by fear, my colleague needn’t have stopped at all. To rationalize stopping and grabbing the Glock, there must be another factor.

The explanation that makes sense to me is that he was mentally visualizing an heroic fantasy script. It’s also what I envisage for something like Kyle Rittenhouse’s rationale. In the fantasy, the noble gun owner leaps to the rescue and emerges with heroic acclaim. It’s what thousands of books, movies and TV programs portray: Everyman turns into Chuck Norris or Rambo … or a video game hero.

Whenever there is a mass shooting, the gun industry and their allies instantly blame video games. They decry how the games warp young minds to normalize gun violence. This, of course, is total hokum and cynical hypocrisy. The gun industry and gun afficionados adore first person shooter games. These games bring the dreams of young “heroes” vibrantly to life … and almost certainly spawn new gun buyers. In fact, the gun industry and culture actively cross-polinates with the video game industry.

- A gun maker steals a video game company’s gun design for its new shotgun (Youtube).

- A breathless review of the real guns that are showcased in Call of Duty video game (Youtube).

If you take the time to watch any of the thousands of Youtube videos reviewing guns, a common thread is the degree to which the presenters breathlessly refer to “bad guys”, “desperados”, “pistoleros”, etc. Recently, Hispanic terms seem very popular … I wonder where that comes from?

Partner with Extremists

If you think about the ideal gun customer, it’s really not the deer-hunting rancher. They probably already have a gun or two that they view as tools. For a gun industry that mass markets dressed up military weapons, various types of extremists present a far more promising demographic. The industry is selling myths and fables, so it’s easy to accomodate another meme that aligns with its goal. For example, the gun industry has eagerly attached itself to evangelical Christians, militias and patriotism. It doesn’t even object to interest from the QAnon and the Boogaloo movements.

Each group and subculture supplies its own free advertising, free indoctrination (for the naive gun buyer), stokes fear mongering, and excites fantasies of heroism. Collectively, it expands the gun culture with an energized, mobilized army of adherents. Ideally, the gun becomes the virtue signal or membership badge for participation in a given group or subculture. The only thing the gun industry must do is to be tolerant of the group or subculture’s goals.

Lobby Politicians to Expand the Pool of Customers

State governments and, now the Supreme Court, have pushed to expand the number of people that are allowed to own and/or carry guns. Many States have lowered the buying age to 18. They have expanded concealed and open carry opportunities. They have passively-aggressively opposed any effort to limit access by people with questionable history or marginal mindsets. Even when they seem to grudgingly acceed to limits, they are careful to maintain backdoors like the gunshow sale loophole, the boyfriend loophole and the short time limit on background checks.

Enforcing Message Discipline

In most durable product industries, message discipline is imposed by the customer. Manufacturers design and manufacture products that cater to customers’ value propositions. If customers want luxurious pickup trucks, manufacturers make luxurious pickup trucks. No one in the industry can force others to make a product they don’t want to make or sell it a certain way. Whatever a manufacturer does, the customers will deliver their judgement and that keeps everyone in the industry more or less in line.

The gun industry is almost the polar opposite. In a practical sense, its customers don’t actually need all that many of its products. The gun industry has to artificially create the perception of need through choreographed and tightly controlled sales messaging. To maintain the fraud, the messaging must stay rigidly consistent across the industry and the gun culture ecosystem. That poses a practical problem. How can an industry enforce message discipline when its marketing stories are mostly mythical, its customers are diverse, and a bunch of companies are competing fiercely to sell similar products?

I suspect that the answer loops back to the Smith & Wesson incident and possibly others. When S&W’s messaging went rogue, the industry proved that it could ruthlessly destroy even a large, iconic gun company. That stopped the Clinton era agreement from being realized and it served as an object lesson for anyone who might later deviate from the industry dogma. I wonder how many times an industry lobbyist, NRA official or gun culture influencer has pulled a well-meaning activist or Republican politician aside and graphically recounted the story of S&W? I don’t have proof, but how else could one maintain a bogus, industry-wide, marketing story. You need a credibly brutal threat to punish potential strays.

The Puzzle Assembled

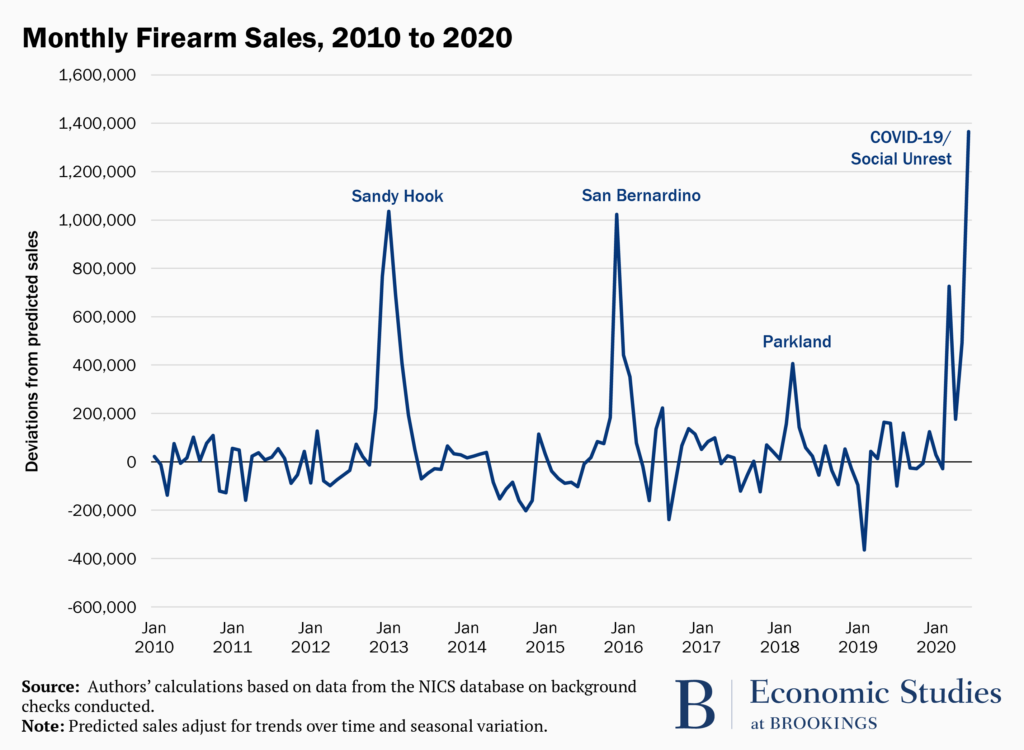

The sales history of the gun industry is not what one would expect for the sale of a durable good that fills a real need and displays meaningful innovation. It’s the pattern for a product that is mostly smoke and mirrors … where a single news day can massively spike sales.

At the start of this post, I posed two mysteries. How can the gun industry survive in such a saturated market and why did it react so violently to Smith & Wesson’s 2000 attempt to “be reasonable”? Hopefully, the answers now seem clear:

- The market for physical guns may be saturated, but the market for irrational fears, heroic fantasies and crazy conspiracies is nearly unlimited.

- To exploit a market of myths and fantasies, the gun industry needs rigid message discipline. The object lesson from Smith & Wesson reinforces the fear needed to maintain it.

For those of us who want to see some form of gun sanity and gun regulation, opposing the gun industry is like chasing a wisp of smoke. Myths and fantasies shift and adjust much faster than political and regulatory tools can track.

We need to rethink our lines of attack and look for weak points that are different from the ones we would exploit in most other industries. I have some ideas that I hope to share in future posts. The Cliffs Notes versions:

- Make the gun industry innovate. Don’t try to ban guns. Make meaningful demands for new safety and/or traceability features. This will drive gun maker/marketers crazy because most of them don’t have the design chops to comply. Demanding features based on chips and AI will drive them nuts.

- To beef up the innovation challenge, demand that certain existing guns (e.g., AR and AK pattern firearms) must be retrofitted with the new features. Since the AR pattern is so modular, it is not technically unreasonable to demand a well-engineered add-on. You can always argue that it will create a totally novel revenue stream for the industry.

- Pass legislation to nationalize the AR patents and re-institute their validity, with the Federal Government as the beneficial owner. Make every gun maker pay a royalty on every gun. Failing to register becomes a flavor of patent infringement.

- Pass legislation to rescind liability waiver for gun makers and require gun user insurance from every gun owner … scaled by the size of their arsenal. Give the insurance industry a new revenue stream and pull them in to help regulate it.

- Offer gun-makers a special path to get into new defence procurement opportunities to replace their gun businesses. For example, offer a gun-maker a 5 year contract to make and/or assemble anti-tank components and weapons (e.g., Javelins) or to assemble attack drones. Guaranteed steady cash flow and profits for a select set of companies that make the transition.

- stuff like that