You have a critical procedure that must be followed across your global operation. You have vendors in China, plants in Portland and Valdosta, offices in Seoul, Stuttgart and Cairo. You relied on emails and memos, but there are differences in practice among the various locations. Is it language? Is it local preference? Are the memos unclear?

Conflicting procedures are almost worse than none at all all. How can you get everyone on the same page – quickly?

The Global Communications Challenge

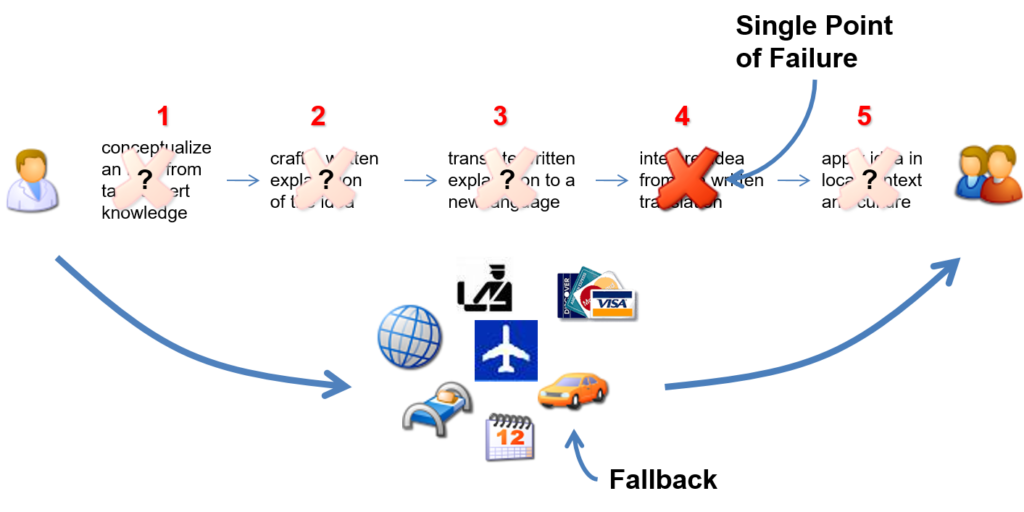

The essential process for communicating across distance, culture and language has been unchanged for centuries. We’ve improved it with technology … we send emails instead of letters. We can use webinars instead of travelling to meetings. Nonetheless, the principles are the same. This diagram shows 5 steps in transferring expert knowledge to a different language and culture. Each step demands a motivated and knowledgeable expert. If knowledge or attention is lacking, the message may not arrive intact.

To an engineer or systems designer, this would raise red flags. Each step is a potential ‘single point of failure’ that can halt the knowledge transfer. Worse, if anything goes wrong at a step, the problem may not be evident until it creates a performance problem at the other end. The fix may require an airplane and an on-site session.

A global, multi-lingual enterprise generates thousands of these communications per week, all with this potential weakness. It’s virtually certain that some communications will fail. In a globalizing world, the problems are real and the solutions costly.

Internet technology can help a bit. It can move the (possibly broken) messages quickly. That may make it easier to fix misunderstandings. Webinars and conference calls can minimize airplane fares. Artificial intelligence translations are getting better … at least for general language.

That can’t make people write coherent explanations. The machine translations will still break down with special vocabulary and context. Finally, the Internet won’t help people match foreign instructions with their local work and culture.

A Fool-Resistant Communication System

Suppose we rework the communication system to place more reliance on video. I’m not talking about entertainment video, I’m thinking about the informal video you get from your smartphone or YouTube.

Instead of trying to craft a manual or procedure, the subject expert “shows and tells” the procedure. Augment that with a colleague who views the demonstration and asks clarifying questions The video is recorded with low-cost video capture technology like your smartphone. Finally, the recording, warts and all, is uploaded and shared from a web server.

The following diagram illustrates the concept.

The communication goes through steps similar to the traditional written approach. The expert’s demonstration is recorded on video by one of several methods. The video clips are transcribed, the narration is edited and voiced over to create a professional English dialog. The English scripts are simultaneously translated and re-voiced in the target language.

The text may be translated to the target language, but the video is constant across every language version. Whatever the video shows is immune to translation error. The viewer will often see translation mistakes as discrepancies and ask for clarification. The video is a powerful safety net for the accuracy of the overall communication.

Compare these two clips … same video with different words and language. Form your own opinion about how much information is in the video and how much in the language-specific narrative.

Video explanations are easier to quality check. In a written translation, the original author may find it hard to verify the accuracy of the translated result. Most Americans can’t read Chinese, so we have to take it on faith that our words were translated accurately. We must judge the behavior that the message inspires at the destination. The translation was good enough if the recipients react the way we expect them to.

With video, we can see a large portion of the message at every step of the process … even when we no longer understand the words. If I know that this is the video clip that was seen in Germany, I know that most of the message got through.

Communicating Visually

One would expect that video would have assumed a central role in global communication by now. There must be forces that have held back its widespread use. Three seem likely:

- People think ‘video is hard to make’. That was true, but smartphones and YouTube have changed that … especially for younger generations..

- Video files are too big to ship. YouTube makes that concern obsolete. As more countries have broadband, that concern goes away.

- Risk and Inertia. The idea in this article is not complicated, but it is a departure from long-held practice. In a conservative business climate, it takes courage to try something this different. Fortunately, it is easy to experiment – and scale up if results are promising.

As industrial video comes into wider use, there is a fourth challenge. Most people are uncertain of their ability to demonstrate knowledge in a visual form. This is a challenge and an opportunity for competitive advantage. If an organization can coach its personnel to use visual tools, they can cut their global communications costs and increase speed and accuracy.

It is important to remember that the message doesn’t have to be completely visual to be effective. The goal is to add a visual communication channel that can cross-verify the conventional audio and textual communication. Over the past 15 years, I have recorded hundreds of informal video clips. Sometimes the message was totally self-evident in the visual presentation. More often, the message was a combination of text, audio and visual elements. Nonetheless, the video component always reduced the risk of misinterpretation. The following examples were all generated by ordinary employees that were not video or graphics experts. To gauge the value of the video content, consider playing these movies with the sound off:

In addition to my experience, some of the best ideas and inspirations can be found at YouTube. Try viewing foreign language videos, or play English videos with the sound off. It is often amazing what you can understand:

- The late Carl Sagan proves that you don’t need special effects to explain something complex – like the 4th Dimension. You just need a tabletop with paper, apples and a clear plastic cube.

- This long screen cast demonstrates how to make a complex graphic with software. The video has no sound, but it still conveys a lot of useful information.

Finally, if anyone is really bitten by the bug of visual explanation, check out books by Edward Tufte. He has published amazing collections that show how to put complex ideas into pictorial forms. Few people will match his insight, but most people will find inspiration and useful ideas. It would take very little effort for an organization to assemble a library of examples and templates to help its staff build better visual explanations.

Bottom Line

If the idea of rapid, error-free, multilingual communication seems appealing, please give us a call and let us help you to explore it. What have you got to lose? If you do global business, you are almost certainly suffering losses every day. This is one of those opportunities where the possible outcomes range between ‘lose very small’ and ‘hit the jackpot’. Those are pretty good investment odds.